Old and the new: First wave of immigration![[Hartford Courant article]](courant.jpg) On 24 October 1915 the Hartford Courant ran a long feature article, "The Colored People who Live in Hartford" that concerned the history of Hartford's Black community. It is interesting that this voice of the white establishment felt it necessary to demonstrate that the old Hartford Black community was a "Peaceful and Orderly Contingent, Industrious and A Credit to City in Which They Live." "Colored people in Hartford in the days of yore seemed to have played their part as factotums to the first families and in contributing to the comfort and convenience of the white folks generally." "Colored people at this time were respected and intelligent and good citizens" (emphasis added). It can be argued that the Courant was trying to reassure whites that, despite the immigrants flooding into Hartford from the South, Blacks were not a threat. Apparently the Courant interviewed various old timers about their recollection of the past, and it seems this recollection was shallow, even distorted, for it was confined largely to some families of the mid-nineteenth century whose members were noteworthy for being subservient. Admittedly, this definition of community in terms of exemplary individuals might simply reflect bourgeois social atomism and the desire to redefine social status in terms of personal career. If there was any real sense of community, either its heirs chose to remain silent about it or the Courant chose to ignore what it was being told. So it may be that a sense of Black community was initially only whites' awareness that some Black individuals happened to reside within the borders of Hartford. The earliest Black known to the Courant was the cobbler Jerry Jacob who lived in the area of Wyllis Street at the time of the Revolutionary War. The Courant mentioned only this tradesman, even though it was obvious that there were Blacks in town well before that, who were the subject of the Black Codes and who acted en masse to petition for their liberty. The Courant was not much interested in Colonial history, however, for it jumps right away to the mid-nineteenth century. At that time lived the Mitchell family, who provided servants and waiters for the white élite, although a Captain Charles Mitchell in about mid-century was New England's only Black tax collector. He received the title of Captain through his Civil War service after having worked at the Courant a number of years. Of course, there was the obligatory mention of Holdredge Primus, who was an exception because he made a "snug sum" prospecting for gold in California. Although he was a businessman, "there was hardly an aristocratic family in Hartford but that had him as door tender or fill some other place at their. . .social functions." If Holdredge's example can be generalized, it seems that one's color made one a servant, regardless of any personal wealth or actual employment. Most people mentioned held small but dignified positions. An example is "Mr. George Smith" (as he liked to be called), who wearing cut-aways served as porter at an important grocery. He may have lived on the Allyn estate. Then there was George Green of Charter Oak Hill, who was valet to Secretary of State, Gideon Wells. At the time of the First World War, there is mention of William Edwards of Adelaide Street, who for forty years was a messenger for the Hartford Fire Insurance Company. Edwards was taken on trips by State's Attorney Brockway, who called him "his adopted boy." There was also Robert L. McCombs of Roosevelt Street, janitor of the high school buildings. James Williams ("Professor Jim") who for forty years was a janitor at Trinity College, then located near where the Capitol building is today (at the left edge of the map below). Then there is C. F. Phillips, who came during the first wave of immigration from Virginia. He was janitor at First Baptist and a deacon at Shiloh. Reverend J. W. C. Pennington was a person of significance as pastor of the Talcott Street Church, but that's was of importance primarily in the Black community. Charles Thomas served two terms as a Capitol messenger. A more remarkable person was B. Rollin Bowser, who was an early beneficiary of political patronage when Governor Hawley, who relied heavily on the Black community for his election, appointed Bowser U.S. Counsul General to Sierra Leone. The Courant finds these people had the virtues of quiet dignity, a disarming smile, and a happy willingness to serve. While Pennington and Bowser enjoyed important posts, most of these Black notables were people of modest status. Alfred I. Plato worked for the Travellers Insurance Company, and " has always been true to the interests of his employers." He married Emma Epps in 1872 and had two children, one of whom, Harry, worked for the Ætna Insurance Company. Edward C. Freeman came to Hartford from Ellington to work for Travellers as a janitor and clerk. He was active in the Talcott Street Church and at one point taught Black children in the A.M.E. Zion Church school on Pearl Street.

However, our recitation of the names usefully reflects the Courant's value system and perhaps even that of the Black old-timers they interviewed, who were themselves apparently rather intimidated by the wave of Black newcomers from the South. There's no mention of communities, such as the Black neighborhoods, or of any collective action such as the petitions or riots of previous years, or of people who (outside their role in the Church) were held in high esteem in the Black community. Someone from the Plato family is mentioned, but not Ann Plato, its outstanding member. While it might seem unreasonable to expect the Courant to rise to our standards of gender equality, the invisibility of women here does reinforce the impression that the notable Blacks of Hartford whom it lists were not selected at random, but reflect the Courant's propagandistic goals. A discussion of Black churches and Black settlements therefore is needed to gain a slighly better idea of what Black social life must have been like after the Civil War. The transformation of Black settlementAlthough hard to define, there are hints that social life for Hartford's Black population

was transformed during and after the Civil War. Before then, many Blacks seem to have often

lived in or near the homes of the families they served, and others were scattered about the City.

The transformation of life in Hartford at the time of the Civil War was marked by an economic shift from riverine commerce to manufacturing, especially war industries. This required a rebuilding of Hartford's infrastructure, the replacement of old wooden buildings with brick construction that was less a fire hazard and could support the weight of manufacturing equipment or a higher residential density of workers near the factories. The resulting crowding, noise and pollution encouraged Hartford's élite to move some distance from downtown, south on Wetherfield Avenue, North on Main Street, and West on Farmington Avenue, where they built substantial estates such as the Samuel Colt mansion and the Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) house on Farmington Avenue. Of course, these enormous houses employed many Black servants. Eventually the rich reached Prospect Street and Blue Hills Avenue, after which they left Hartford altogether. Old areas were torn down and new construction along railroad lines (Capital Avenue, Park Street, Homestead, Windsor Street) was built for manufacturing, with "perfect six" working-class housing built in surrounding areas. Although the downtown area was to experience another transformation after 1957 with the shift from manufacturing to a service economy, much of the physical remains of the old industrial Hartford remain to be seen today. That cannot be said of Hartford's earlier manifestations.

Much of the downtown was converted from mixed use to the support of light industry during and after the Civil War. A catalyst for this transformation was the construction of Bushnell Park. It was to offer a virtual reality substitute for nature in the raw as a counter to the noise and pollution arising from Hartford's incipient industrialization. By displacing the Black community from the Park River, it reduced "social pollution" as well. The growth of industrial emploment opportunities and housing drew to Hartford quite a different population of Blacks than the harmless old timers so admired by the white establishment. The end of Reconstruction meant an increase in social hostility and economic hardship for Blacks in the South, and this resulted in a first wave of Black migration from southern farms to the North after the Civil War. This is usually distinguished from a second wave of migration that began shortly before the end of the century and steadily mounted until the local economic downturn in the final decades of the twentieth century. This first immigration seems to have had relatively limited social impact, for in 1915 it was assumed that it only resulted in a growth in the Black population from about 1000 to 4 or 5,000, although these figures include the beginning of the second wave of migration. Whites preferred not so see this new working class which found employment in construction and perhaps even industry, and kept their mind's eye on the older and more malleable population. Immigrants tend to form a community in order to buffer their members' relation with a social environment that is at best alien and at worst downright hostile. So these newcomers after the Civil War were likely to settle within Black community rather than scatter, but because of the destruction of the original Black community along the Park River, they located themselves in what was then the northern part of the city (the 4th, or originally the 7th ward) and on Windsor and Front Streets.

The map may be a little confusing because at the time Main Street extended only to the beginning of Albany Avenue, where it continued north as "Windsor Avenue." That apparently led to confusion with Windsor Street, and so Windsor Avenue was renamed as an extension of Main Street. The second Black settlement was along Windsor Street, which ran from Talcott up to the railroad line behind SAND. At some time in the 19th century it was extended further north to parallel the railroad spur as a new industrial area. Apparently there's no trace left of this important Black community behind what is now the Hartford Graduate Center. In recent times Hartford has benefited from a handful of individuals who have fought for architectural preservation. Such tangible manifestations of our history are important because they serve to locate us as part of a tangible process that existed in time and therefore locate us also as agents of the change implied by that process. The Black community is now acquiring a tangible expression of its own history in Hartford through the African-American Monument Project. Not many in the City today are descended from those slaves and servants buried at the edge of the Park River Black community, but consciousness of the transformation of that community helps liberate our mind from the prison of an eternal present. That start at the Ancient Burying Ground needs to be carried forward, though, for undoubtedly there are significant archæological remains of the three communities discussed here. In particular, it would be fruitful to investigate Bushnell Park just south of the bend in the Park River (just East of the pond today), for here there was probably less disturbance because of subsequent building construction. The Black ChurchesIn the nineteenth century there were five Black churches. That number was probably due more to the variety of beliefs than a reflection of the number of Black neighborhoods in Hartford. Although the Front Street Black Neighborhood was not the oldest, its Talcott Street Congregational Church (the "African Church") built in 1823 is said to be the first Black Church in the city. Presumably the Black population in Hartford until then relied on the white churches if they went to church at all. One suspects that the Talcott Street Church probably arose as a result of the formation of a sense of Black community in Hartford, for it was not only associated with the riot of 1835, but later with the abolitionist movement in the Black community. So, while the Park River Black Neighborhood was probably older, it was perhaps socially less viable than the Front Street Black Neighborhood that arose near all the shipping activity along the Connecticut River.

We associate the Baptist religion with the wave of southern migration, and indeed, Shiloh Baptist (not at its present location) was established in 1889. Thanks to the first wave of migration, it became the largest Black Church in Harford and prospered around the time of World War I. The Union Baptist Church, was built on Mather Street a little earlier in 1871. Further investigation might show that while the target of the first wave of southern migration was the Windsor Street Neighborhood, it grew to include the early settlement near Mather Street and what had been called "Nigger Lane." There was also built on Mather Street St. Monica's Episcopal Church in 1912. The absense of an earlier church in the area might be because folk went to the Talcott Street Church, which was closer. Problems to be resolvedThis feeble attempt to trace the outlines of Black social transformation in Harfford after the Civil War needs development through further study. Here are some of the missing dimensions that perhaps some enterprising students might tackle:

|

![[Chester Stanton]](stanton.jpg) The Courant's list is long and boring, as it is meant to be in order to achive its desired effect.

Generally the people it cites are not the forebears of today's Hartford families nor people who were in

any way really remarkable. The cabbie Chester Stanton, for example, was very active in Hartford,

driving people from Union Station in the 1890s (photo of a tin type in the possession of Stanton's

descendent, Thirman Milner). Stanton was well known to Hartford's élite, for he was a "water

boy" for the Governor's Foot Guard. It is not that more remarkable people didn't exist in Harford.

The Courant's list is long and boring, as it is meant to be in order to achive its desired effect.

Generally the people it cites are not the forebears of today's Hartford families nor people who were in

any way really remarkable. The cabbie Chester Stanton, for example, was very active in Hartford,

driving people from Union Station in the 1890s (photo of a tin type in the possession of Stanton's

descendent, Thirman Milner). Stanton was well known to Hartford's élite, for he was a "water

boy" for the Governor's Foot Guard. It is not that more remarkable people didn't exist in Harford.

![[Map of area of original Black community in Harford]](hfd-1.jpg) However, it was the

recollection of Black people in Hartford (see the Hartford Courant, feature article)

that there had been

an early and perhaps original Black community in the area of Gold, Lewis, Hicks and Pearl Streets.

On this 1854 map, the community would have stretched along the north bank of the Park River,

probably facing the island at the upper left.

However, it was the

recollection of Black people in Hartford (see the Hartford Courant, feature article)

that there had been

an early and perhaps original Black community in the area of Gold, Lewis, Hicks and Pearl Streets.

On this 1854 map, the community would have stretched along the north bank of the Park River,

probably facing the island at the upper left.

![[Gold Street]](gold.jpg)

![[Hartford map 2]](hfd-2.jpg) This map gives some idea of the areas. At the lower right, parallel to the River runs Front Street, which

was left in a state of decay rather than rehabilitated, probably because it had lost its economic function with

the decline of the riverfront docks. Serving this neighborhood was the "Afric.Ch" seen one block

west at the corner of Talcott and Market Streets. This neighborhood was a slum that became

a dumping ground for new immigrants, particularly Jews and Italians. This vibrant multi-racial

and multi-ethnic heart of the city, the East Side or Bottems, as it has been called (where the police

were careful to locate their station), was destroyed by the construction of Constitution Plaza in

1957, and the City never recovered.

This map gives some idea of the areas. At the lower right, parallel to the River runs Front Street, which

was left in a state of decay rather than rehabilitated, probably because it had lost its economic function with

the decline of the riverfront docks. Serving this neighborhood was the "Afric.Ch" seen one block

west at the corner of Talcott and Market Streets. This neighborhood was a slum that became

a dumping ground for new immigrants, particularly Jews and Italians. This vibrant multi-racial

and multi-ethnic heart of the city, the East Side or Bottems, as it has been called (where the police

were careful to locate their station), was destroyed by the construction of Constitution Plaza in

1957, and the City never recovered.

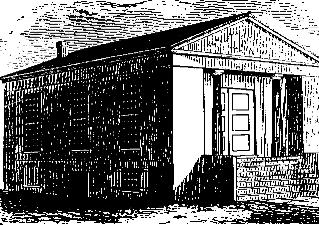

The other primary "African" church in Hartford was the American Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (African),

which was established in 1836 at 269 Pearl Street to serve the needs of the nearby Park River Black

Neighborhood. In 1857 the church was rebuilt at 91 Pearl Street. The building shown in this lithograph from

Geer's Hartford Directory (Connecticut Historical Society Library) is identified as the new church,

but on architectural grounds it seems more likely to be the original building of 1836. It was built

for $6000 and could seat 445 people. Although it might seem modest today, it was at the time among the

City's major constructions.

The other primary "African" church in Hartford was the American Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (African),

which was established in 1836 at 269 Pearl Street to serve the needs of the nearby Park River Black

Neighborhood. In 1857 the church was rebuilt at 91 Pearl Street. The building shown in this lithograph from

Geer's Hartford Directory (Connecticut Historical Society Library) is identified as the new church,

but on architectural grounds it seems more likely to be the original building of 1836. It was built

for $6000 and could seat 445 people. Although it might seem modest today, it was at the time among the

City's major constructions.

Here in fact is the new A.M.E. Zion church, but in the Italianate style one might expect for 1857. It stood

at the southwest corner of Pearl and South Ann Street, right at the northern edge of the old Park River

Black Community. At the left of the photo we look south down Ann Street, which ended a block away

at the Park River. So we would be looking right into Hartford's oldest Black community, except that by

the time this picture was taken in June 1898, the entire neighborhood had been displaced and the church

was being relocated to North Main Street. The building seen to the right of the church was the fire

department which now occupies the land on which stood the church.

Here in fact is the new A.M.E. Zion church, but in the Italianate style one might expect for 1857. It stood

at the southwest corner of Pearl and South Ann Street, right at the northern edge of the old Park River

Black Community. At the left of the photo we look south down Ann Street, which ended a block away

at the Park River. So we would be looking right into Hartford's oldest Black community, except that by

the time this picture was taken in June 1898, the entire neighborhood had been displaced and the church

was being relocated to North Main Street. The building seen to the right of the church was the fire

department which now occupies the land on which stood the church.