Born in Struggle, 1819-1860:

Movements for change

|

|---|

|

Because solidarity is

the only way to struggle for progress which is available to people who are

not the owners of productive property, popular struggles become an important symptom of social

development when more direct evidence for it is lacking. While there are some indications of struggle

by Hartford's Black community, it was neither persistent nor very impressive prior to the Civil War.

Congregated housing could be a locus for community building, but certainly another was the Black Church.

Pioneering in this respect is the Talcott Street Congregational Church, which was located at the corner

of Talcott and Market Streets, near an early Black community on Front Street. While this "African Church"

as it was called in mid-century, may have been Hartford's oldest Black Church by several years, the

Park Street community may have been older. The original location of this church, is today marked by a

bronze plaque.

Congregated housing could be a locus for community building, but certainly another was the Black Church.

Pioneering in this respect is the Talcott Street Congregational Church, which was located at the corner

of Talcott and Market Streets, near an early Black community on Front Street. While this "African Church"

as it was called in mid-century, may have been Hartford's oldest Black Church by several years, the

Park Street community may have been older. The original location of this church, is today marked by a

bronze plaque.

The Talcott Street Church was founded by the African Religious Society and soon contributed

to the formation of the Black community in Hartford. It did so by becoming a center for abolitionist

and social activity in the Black Community. In its basement was Hartford's first Black school, and not

surprisingly, from this church community arose many of the leaders who would eventually shape the

community's future.

The Talcott Street Church was central to a racially-based riot in 1835. We use the term

"race riot" today, but things are not really that simple. First of all, it is the consensus of modern science

that there is no such thing as "race." This is because our genetic inheritance is part of a broad spectrum

of traits, so that it is impossible to sort people into neat categories. For example, there are all shades of

skin color found among Black siblings, not just because of descent from a white ancestor, but because

people of African descent have greater genetic diversity than any other people. The notion of "race"

was socially constructed by the ruling class at a time when the essential quality of all living things was

assumed to be "preformed" in a microscopic or ideal model contained in their seeds, so that their

"essence" is somewhat independent of appearances. The type from which humans arise was called the

"homunculus," and from there it was but a small step to suggest that some "homunculi" are essentially

superior to others.

So it is only with nineteenth century biological racism (so-called "scientific racism") does the idea

appear that some people are Black in essence while others are essentially white. Racism was a peculiar

notion that only became significant because it served the ruling class as a very useful means to

exploit working people by dividing them on some imaginary basis. It was clearly fictional, for very light

skinned people were considered to be "Black," while dark-skinned Mediterranean people are defined

as "white." This tactic long suceeded in preventing the solidarity between white and Black working people

that might have resulted in significant social change.

|

Apparently, the Talcott Street Church was a point of contact between white idealists who objected

to slavery in the United States on moral grounds and the Blacks whom they felt would be their natural

allies. This contact, however, may have been less significant than the response of Blacks to a real local

threat, the attack upon the Black community by whites.

Apparently, the Talcott Street Church was a point of contact between white idealists who objected

to slavery in the United States on moral grounds and the Blacks whom they felt would be their natural

allies. This contact, however, may have been less significant than the response of Blacks to a real local

threat, the attack upon the Black community by whites.

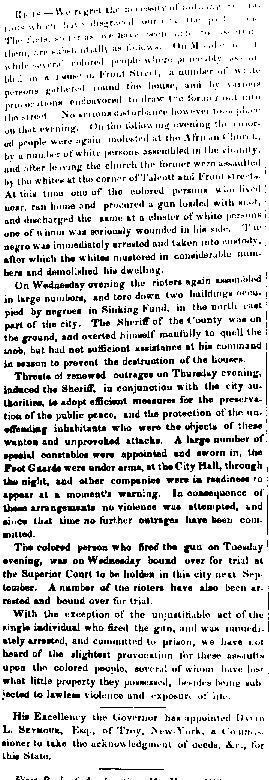

As this column from The Hartford Courant of 15 June 1835 points out, earlier

in that week a group of whites had tried to provoke some Blacks who had gathered at a house

on Front Street. While nothing came of it that evening, the event suggests that whites felt so

insecure they found it necessary to attack the Black community and initiate a series of riots.

A review of US labor history during those years would suggest ample reason for white

working-class dissatisfaction and insecurity and for their employers to seek desperately for some way

to divert it away from themselves. All that was needed to do this was biological racism. Such attitudes

were neither spontaneous nor in any way natural, but were invented by bourgeoisie intellectuals. That

the incident became something more than a simple confrontation was evident the following evening.

Some Blacks had gathered at the Talcott Street Church. While we can't be sure this meeting was

called in self-defense, it should be noted that the Church offered a convenient and natural place for

the Black community to meet. However, a white gang soon gathered outside and attacked

Blacks at the corner of Talcott and Front Streets (now the corner between the G. Fox

building and the G. Fox garage) as they left the Church.

One of the Black people who lived nearby ran home and to procure a gun and fired it at the

white crowd, wounding one person. As a result, the white crowd went to the Black person's home and

demolished it. Wooden houses on Front Street were not very substantial, it seems, and it was assumed

that the homes of Blacks were particularly modest affairs, not much more than what we would today

call a shack. Nevertheless, in bourgeois society, to destroy someone's property in effect emasculatesd.

This incident caused a much larger crowd of whites to gather the following evening, and it

walked north to destroy Black homes in the "Sinking Fund" (apparently the suburb outside the City

just north of Belden Street). This civil disorder proved to be too much for the white authorities, and

so the Sheriff mobilized the Footguard for the following night, and apparently this sufficed to end

any further disturbances. Says The Courant, "we have not heard of the slightest provocation

for these assaults upon the colored people, several of whom have lost what little property they

possessed, besides being subjected to lawless violence and exposure of life."

|

Another situation that suggests the Black community lacked the solidarity to bring about change

was the struggle in the State to abolish slavery. While the Civil War decided the issue of slavery

for the United States as a whole, in Connecticut itself the abolition of slavery passed into law in

1838 as the result of a lawsuit brought by a Black woman. Even the mass pressure brought to bear

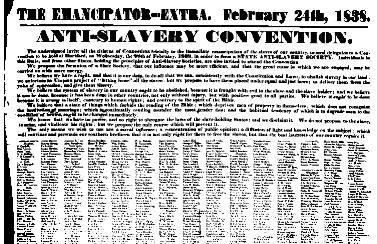

in support of this victory was not that of the Black community. For example, shown here is a

broadside, The Emancipator-Extra of 24 February 1838 (Simpson Collection, Wadsworth

Atheneum), bearing the names of supporters thoughout Connecticut for the calling of a convention

in Hartford to be held on 28 February 1838 to form a State Anti-Slavery Society. As the names

appended here show, the movement did not consist of Black people.

Another situation that suggests the Black community lacked the solidarity to bring about change

was the struggle in the State to abolish slavery. While the Civil War decided the issue of slavery

for the United States as a whole, in Connecticut itself the abolition of slavery passed into law in

1838 as the result of a lawsuit brought by a Black woman. Even the mass pressure brought to bear

in support of this victory was not that of the Black community. For example, shown here is a

broadside, The Emancipator-Extra of 24 February 1838 (Simpson Collection, Wadsworth

Atheneum), bearing the names of supporters thoughout Connecticut for the calling of a convention

in Hartford to be held on 28 February 1838 to form a State Anti-Slavery Society. As the names

appended here show, the movement did not consist of Black people.

Besides the fact that other [bourgeois] countries had already abandoned slavery, the

broadside significantly notes that the objectionable features of slavery are that it forbids the reading

of the Bible, it prevents people from acquiring property, and does not recognize the institution of

(slave) marriage (which civilizes man). In other words, slavery is really incompatible with the

bourgeois order. Although moral principle and human compassion were undoubtedly present here,

the basis of the Connecticut bourgeoisie's objection to slavery was its incompatibility

with the order support its domination.

|

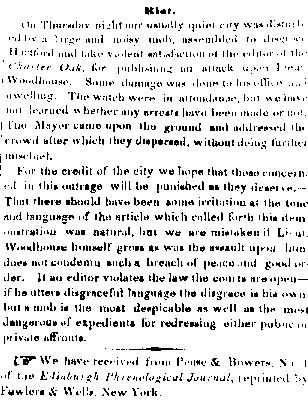

The abolitionist newspaper, the Charter Oak was also a target of attack. The article here

from another paper reports the second of Hartford's two major riots associated with Blacks, although

in this case Blacks were not directly involved. The paper reports that a white mob attacked the office

of the Charter Oak because its editor had launched an abolitionist attack on a Lieutenant

Woodhouse. The watch (in effect, police) were on the scene and then the mayor himself, and this

apparently sufficed to disburse the crowd. The article reflects the bourgeois ruling class objection to

disorders of any kind and for whatever cause, whether just or not, because it disturbes commerce.

The abolitionist newspaper, the Charter Oak was also a target of attack. The article here

from another paper reports the second of Hartford's two major riots associated with Blacks, although

in this case Blacks were not directly involved. The paper reports that a white mob attacked the office

of the Charter Oak because its editor had launched an abolitionist attack on a Lieutenant

Woodhouse. The watch (in effect, police) were on the scene and then the mayor himself, and this

apparently sufficed to disburse the crowd. The article reflects the bourgeois ruling class objection to

disorders of any kind and for whatever cause, whether just or not, because it disturbes commerce.

Interesting is the beginning of the next entry in this newspaper column because it reflects a racism

of a different sort. It is a notice of a reprint of the Edinburgh Phrenological Journal. Phrenology

was the belief that the shape of a person's skull manifests features of the underlying brain and hence the

person's inherent character and mental capacity. That is, one's essential character is a reflection of one's

inherited genes, and this is exactly what the new racist ideology was claiming. The notion of the inherent

(genetic) inferiority of Blacks was not an isolated phenomenon, but one based on an atomistic reduction

of the human being to inherited (immutable) physical characteristics. The popularity of such notions lent respectability to ruling class efforts to divide working people on racial lines and to exploit Blacks to a

greater extent than whites workers would themselves accept.

One might be tempted to conclude that abolition was largely a white concern, but such was not

the case. The late eighteenth-century petitions by Blacks in the state to abolish slavery shows that Blacks

took it very seriously. Furthermore, there were several notable Blacks who took a leading role in the

abolition movement.

For example, Augustus Washington travelled to Africa with the hopes of setting up

a colony to which American slaves might emigrate. Emancipated slaves in the British colonies

had already been repatriated to Sierra Leone in West Africa,

and in 1822 some free Blacks from the Unites States were sent by the American Colonization Society to

to Africa to start a new life there, despite the skepticism of most Blacks who by this time felt that the

United States was their real home. This colony, which was given the name Liberia, did not fare well and

the American Colonization Society abandoned them. The colony was saved from complete failure by the

energies of a young white New England abolitionist, Yehudi Ashmun, who went there in 1828 and through considerable effort helped the colony survive, although just drifting without any direction. Little further

help came from the U.S., and Liberia was very small and weak in 1847 when its independence was

recognized in law. However, by this time it had lost any appeal to American Blacks.

|

After August Washington, the Hartford Blacks who joined the abolitionist cause no longer favored

emigration to Liberia, but winning civil rights for the City's Black population, legally free since the end

of servitude in the State in 1838.

After August Washington, the Hartford Blacks who joined the abolitionist cause no longer favored

emigration to Liberia, but winning civil rights for the City's Black population, legally free since the end

of servitude in the State in 1838.

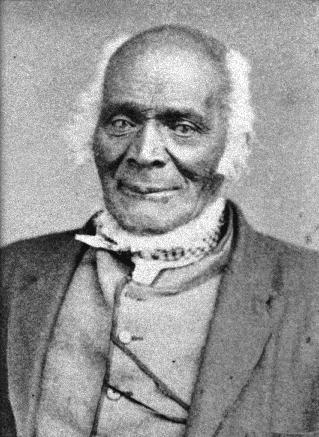

One notable figure in this regard was James Mars. He was one of those whose service in the

Revolutionary War led to the pursuit of a professional career, and entering church office must have offered

the fewest hurdles. Mars became a deacon at the Talcott Street Church and actively sought the reform

of Connecticut and national legislation affecting Blacks. During the 1840s and 50s he organized several

petitions to the Connecticut legislature regarding voting and social rights for Blacks.

In 1864 he wrote, "Connecticut - I love thy name, but not thy restrictions. I think the time is not

far distance when the colored man will have rights in Connecticut." Indeed, these rights would come, but

it took a century, and social justice remained allusive.

In this and the next case, it is interesting to note that Blacks who acquired status and influence

through holding office in the Talcott Street Church were inclined to join the white abolition movement.

Surely interest in abolition must have extended to less privileged Blacks in Hartford, not so much for

the abolition of slavery itself, which must have seemed a rather abstract issue here, but as a vehicle

for demanding civil rights.

|

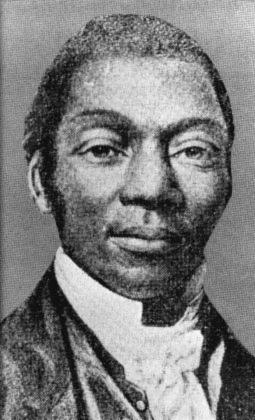

Mars was a native son, but another notable Hartford Black abolitionist, J. W. C. Pennington, had

started as a slave in Maryland. He fled as a young man to Connecticut because slavery had been

abolished here, and he eventually became a minister at the Talcott Street Church. He studied at

Yale and also later during a stay at the University of Heidelberg, Germany. Pennington was an

abolitionist lecturer, and as a representative of the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society and Union

Mission Society, he spoke throughout the Northeast and in Europe.

Mars was a native son, but another notable Hartford Black abolitionist, J. W. C. Pennington, had

started as a slave in Maryland. He fled as a young man to Connecticut because slavery had been

abolished here, and he eventually became a minister at the Talcott Street Church. He studied at

Yale and also later during a stay at the University of Heidelberg, Germany. Pennington was an

abolitionist lecturer, and as a representative of the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society and Union

Mission Society, he spoke throughout the Northeast and in Europe.

Shown here is a photograph made in about 1860 and which appeared in William F. Henney,

Hartford: Commonwealth of Connecticut.

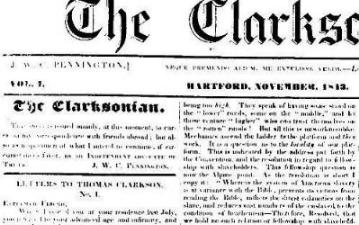

One of Pennington's interesting efforts was his publication of an anti-slavery newspaper

called The Clarksonian. The first issue was published in 1843, and it was intended as a

means to keep in touch with fellow abolitionists during his travels. The first issue begins with a

long letter to Thomas Clarkson of Ipswich, England, and hence the name. Copies of this paper are

very scarce, which is a shame, for it would be an excellent source for the history of the abolition

movement.

|

Pennington notes here that the most significant development in Connecticut affecting aboltion

since the "great Amistad case" was the Christian Convention held in June 1842, and another held in

Middletown in October 1843. The aim of these conventions was to unite white people around the abolition

issue without becoming sidetracked by "various frivolous disputations such as woman question, &c." He

further notes that many [white Christians] who are not avowedly abolitionists are ashamed of direct

opposition."

Nevertheless, he observes, "At the outset in this cause the ministers did not take the lead as they

are expected to do on every great question of morals; nor did Christians generally take a part as such."

Pennington does mention his fellow Blacks when he says, " I am still more seriously convinced of the

necessity and obligation resting upon colored men to speak and write freely for themselves." However,

the point serves only as an excuse for having "laid off my modesty as a moth eaten garment" to "speak

and write freely for myself." Nothing is clear from this that he saw Blacks per se as agents

of change.

A a later point, Pennington reponds to the question about how the anti-slavery cause is advancing

by saying, "Not rapidly, but I think it is gradually laying firm hold on the conscience of the nation." He feels

that the first step is to persuade Churches and ministers to preach that slavery is sinful. Again, the engine

of change is the moral arguments of the elite rather than the solidarity of ordinary Blacks.

|

![[Exhibit contents]](../../bin/top.gif)

![[Back]](../../bin/back.gif)

![[Forward]](../../bin/forward.gif)

|