Citizens of Color, 1863-1890:

Black Labor: Military Service

|

|---|

Union veterans returing from the

Civil War formed an organization called the Grand Army of the Republic.

The Mansfield Post in Middletown was quite active, and it included a number of Black Hartford veterans.

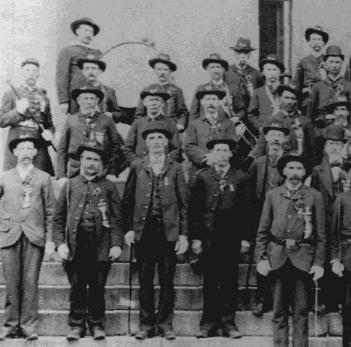

Shown here is a detail from a photography of the members of Mansfield Post #53 in c. 1880 (Connecticut

Historical Society Museum Collection). The photograph shows about 100 veterans, and it appears that

about five to ten percent of them were Black.

Union veterans returing from the

Civil War formed an organization called the Grand Army of the Republic.

The Mansfield Post in Middletown was quite active, and it included a number of Black Hartford veterans.

Shown here is a detail from a photography of the members of Mansfield Post #53 in c. 1880 (Connecticut

Historical Society Museum Collection). The photograph shows about 100 veterans, and it appears that

about five to ten percent of them were Black.

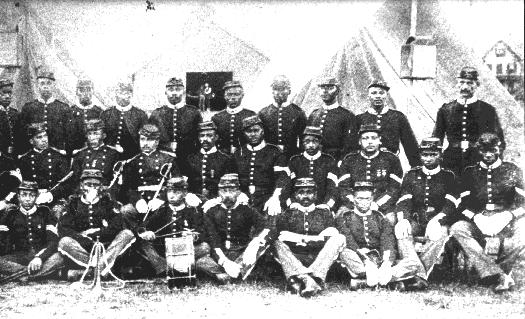

Military service had long attracted Blacks, and the two Connecticut Infantry Regiments have already

been discussed. The 29th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment mustered out in Hartford on 14 October

1965, but its veterans remained in touch, probably through such organizations as the Grand Army of the

Republic. They eventually decided to petition the State to form a National Guard unit of Black members.

On 27 May 1879, the 5th Battalion, Colored, of the Connecticut National Guard, was formed. The Hartford unit

in the Battalion was Company B, led by Captain Lloyd Seymor. This illustration shows part of a photograph

of this "2nd Separate" National Guard Company" from Hartford, in about 1892 (loan from the Connecticut

Afro-American Historical Society).

|

Menial and domestic labor

In most Connecticut towns, while a lucky or talented few might achieve respectable social rank, most

Blacks population until this time would have been employed in domestic labor, which to some extent must

not have been clearly distinct from slavery to either master or servant. The alternative, for males, would

have been simple heavy labor. For example, at the southern edge of New Britain, where today there are

ponds next to the highway, there was one of the brick works that supported the post Civil War building

boom. The cove just south of Wethersfield Cove was another. The New Britain brickworks employed a

significant number of Blacks, while their wives usually worked in town as domestic servants. This was

undoubtedly the case in Hartford as well. While this example suggests that Blacks might benefit from

the prosperity resulting from the War, but their jobs did not represent the first rung of a career ladder,

as was the case of most immigrants to this country, for growing racism tended to force everyone of

color to remain at the bottom rung without hope of an eventual rise.

The development of Hartford as a center of light industry called for a range of services in which

Blacks might find employment. Because many places of concentrated employment were some distance

from home (this was before the trollies were built), lunch became a problem. Most workers probably

brought lunch with them to work, but the Ladies of Hartford felt that the male nature needed

domestication and lunch should be separated from the workplace, which was considered unhealthy for

mind, body and spirit. Hence the word restaurant literally means that the person going to it is restored.

So the Ladies ran a restaurant for workers so that they might eat in a domestic-like atmosphere in

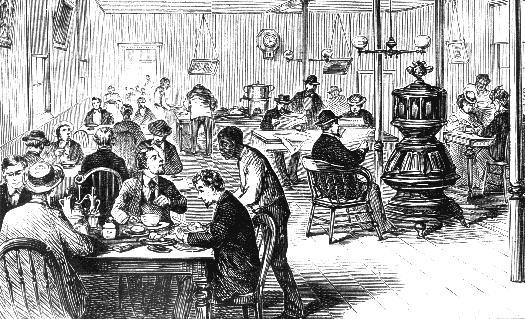

which nutrutious meals were available for modest cost. The lithograph below is of a sketch done by

H. C. Curtis in 1872. It shows their Workingmen's Restaurant" (Connecticut Historical Society Museum).

However, we need to consider all dimensions of the rise of restaurants. It appears here that

the waiters were Black, for such a job represented one step above being a domestic servant and

required much the same skills. On the other hand, the patrons are apparently all white. But note

carefully. They do not seem common laborers, who would be dressed in rough work clothing, but

well-dressed workers who read the newspaper. Although not much separated white and Black

workers in terms of income or the kind of work done, in this restaurant is reproduced the old

relation of slave and master. And as racism solidified this social divide, employers had little to

fear that white and Black labor might struggle together in their common interest (it had happened

not long before in the Knights of Labor).

Shown here is part of a 1908 photograph done by J. C. Dexter Co., Photographers, of work

being done on buildings probably originally built two or three decades earlier on lower State Street.

This view seems to look West from the intersection of State Street and Front Street - now Columbus

Boulevard (Connecticut Historical Society Museum). Pictured here is a Black workers, perhaps a plasterer.

State Street ran from the Old State House to the City's early life line, Commerce Street (today

largely displaced by the dike and Route 91) which connected the docks that jutted out into the Connecticut

River from Dutch Point up past Morgan Street to Pleasant Street. Before the Civil War, this commercial

activity offered employment, and so many of Hartford's Blacks lived on Front Street, a residential area

that paralleled Commerce Street, running from the Mill River (now the underground Park River) in Dutch

Point north to Pleasant Street. Although the Hartford and Springfield Railroad eventually built a spur to

its Commerce Street freight depot, the inevitable trend was for rail transportion to replace canals and

rivers as the principal way to carry goods. This drew the best jobs away from Commerce Street to the

streets that came to radiate from downtown along rail spurs, such as Windsor Street, and Homestead,

New Park, and Capital Avenues. While the better were no longer downtown, it did mean an expansion

of service sector and menial labor employment downtown, not far from the Black community living on

Front Street.

These generalizations regarding Hartford's early economic development require much further

study, particularly the relationship between economic change and patterns of Black residence and

employment. In the expanding economy after the Civil War, there is good reason to think that

employment opportunies multiplied, but the increasing segregation of the workforce on sexual

and racial lines to prevent labor solidarity intensified the exploitation of not only Black and female

labor, but ultimately more skilled white labor as well. Unfortunately, the early AFL tended to reflect

this and aimed to defend the relative advantage of white labor against Black and female labor, not

realizing that a divided labor ended by working against the interest of everyone.

|