For most Blacks, it should have been quite evident not only that their successful rise into the

bourgeosie was improbable, but the new political order was establishing barriers to make it nearly

impossible. The bourgeoisie had give reason to a broader segment of the people to support their

revolution, but when it came time to write the state constitutions, that promise was betrayed.

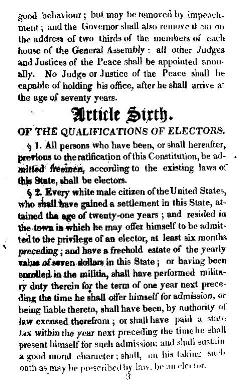

Here is the sixth article of the Connecticut State Constitution of 1818 that defines

voting qualifications (photocopy of original in the Connecticut Historical Society Library). Section

one was a grandfather clause that protects the voting rights of all persons who are freemen prior

to the Constitution's ratification. However, section 2 specifies a list of hurdles that a person must

jump in order to vote: he must be white, male, twenty one, a town resident six months, and own

real estate of a certain minimum value or have performed military service, or paid property taxes

to the state, etc. Women and Blacks were therefore excluded from having political power, and

so too were those not owning significant property. For most Black people, then, the only way to

achieve dignity and some influence over the course of affairs would be to organize outside the

political system. This could only take place on the basis of Black community. Here is the sixth article of the Connecticut State Constitution of 1818 that defines

voting qualifications (photocopy of original in the Connecticut Historical Society Library). Section

one was a grandfather clause that protects the voting rights of all persons who are freemen prior

to the Constitution's ratification. However, section 2 specifies a list of hurdles that a person must

jump in order to vote: he must be white, male, twenty one, a town resident six months, and own

real estate of a certain minimum value or have performed military service, or paid property taxes

to the state, etc. Women and Blacks were therefore excluded from having political power, and

so too were those not owning significant property. For most Black people, then, the only way to

achieve dignity and some influence over the course of affairs would be to organize outside the

political system. This could only take place on the basis of Black community.

There are indications that Black community formation was taking place in spite of forces

working in the opposite direction. One indicator would be the proximity of Black homes. Unlike

today, when "property" means anything having intrinsic cash value, around the time of the American

Revolution it specifically referred to income-producing property. That is, property was not just a

thing in itself, as in its present meaning, but also implied an economic relation to others in the

community, your customers and employees. Therefore mere home ownership did not represent

an ownership of "property," and therefore it did not carry with it the civic rights associated with

property ownership.

Nevertheless, owning a home did mean some degree of economic independence from the old

paternalistic ties, and so opened the way for the formation of social bonds within the Black

population.

Nevertheless, owning a home did mean some degree of economic independence from the old

paternalistic ties, and so opened the way for the formation of social bonds within the Black

population.

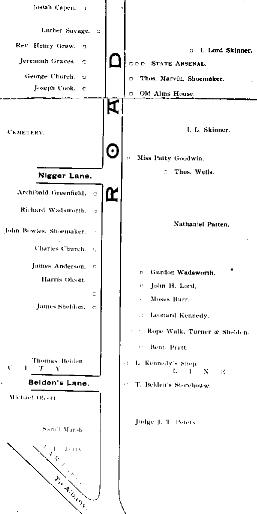

Shown here is an 1825 map of the area just to the North of Hartford, along the "Road to

Windsor" (from Gordon W. Russel, "Up Neck" in 1825.)

At the bottom, running northwest, is the road "To Albany." If modern Windsor Street was created

later as an industrial shortcut, then this road to Windsor would be modern North Main Street. The first

street north of the road to Albany was Belden's Lane (now Belden Street). In 1825 it marked the northern

extent of the incorporated city of Hartford. In other words, this map is of suburbs, although there were

already commercial properties scattered among the homes of many of the city elite, safely above the

North Meadow flood plain to the road's east. At the top of this map is the home of Josiah Capen, which

marks what is now Capen Street.

Today, between Belden and Capen Streets lie two important streets that also run west: Mather

Street and Mahl Avenue. Mahl Avenue is in effect an extension of Greenfield Street, and indeed, on the

map is shown the home of Archibald Greenfield. From that point, running West in 1825, was "Nigger

Lane" supposedly because there were some Black-owned homes there. It is said that this street was

later renamed Pine Street before becoming Mather Street, but more likely it was today's Mahl Avenue.

It seems that by this time there were neighborhoods in which Black homes were concentrated. An

early one was apparently a group of homes on the banks of the Park River between what is now

the Bushnell Park pond and the old stone bridge that allowed Main Street to pass over the river.

This was once the longest stone span in the New World, but has lost that honor and today serves

only to separate the cars on the highway below from the books stored above (in main branch of the

Hartford Public Library). The community's subsequent destruction to build the Country's first urban

Park may be the earliest example of the use of "Urban Renewal" in the US to destroy undesirable

communities.

There is reason to suspect that the beginning of the North End Black community may be found

in this Nigger Lane just north of the 1825 city limits, but these speculations about early Black

communities need considerably more research such as an archaeological dig under the northwest corner

of Bushnell Park. In any case, with a Black community in place, struggle for change could begin to take

place.

|