Emerging from the Shadows, 1775-1819:

Blacks in the Revolutionary War |

|---|

The American Revolution was not broadly

supported by whites, and the revolutionary leaders, who

acted out of their commercial interest, found it difficult to recruit anyone else to fight for them. For

example, it was necessary to promise political rights to "Sons of Liberty" recruited from Boston workers,

and farmers in Massachusets were offered Indian land in upper New York state as a bribe. Not surprisingly,

then, especially since there was no real conviction that Blacks were inherently inferior, the white ruling

class recruited Blacks to be fighters and die for their cause.

Connecticut was rather slow to bring Blacks into its militias, and so Blacks who sought to gain

land or freedom through the war had to join the militias in neighboring states. For example, the Black

Rhode Island Regiment fought at the important Battle of White Plains.

Connecticut was rather slow to bring Blacks into its militias, and so Blacks who sought to gain

land or freedom through the war had to join the militias in neighboring states. For example, the Black

Rhode Island Regiment fought at the important Battle of White Plains.

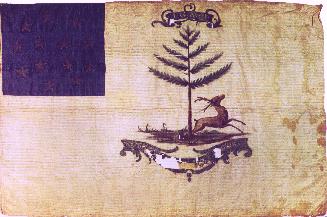

Shown here is the flag of the Bucks of America, c. 1786, (Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

which was a Massachusetts unit that was almost entirely Black. At the upper left is a square with the gold

stars of the thirteen original colonies on a blue ground, and a buck is leaping near a pine tree. Many members

of this unit came from Hartford and elsewhere in Connecticut before Blacks were allowed into the

Connecticut militia.

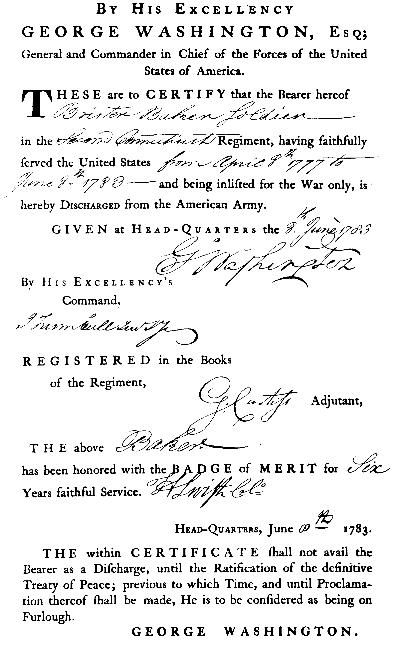

Copy of the Honorable Discharge for Brister Baker, 1783, from Colored Patriots of the American

Revolution, by William C. Nell. Brister Baker was a Black soldier who fought in the Second Connecticut

Regiment. The meritorious discharge notes that Baker was enlisted into the Army in April 1777 and served

six years faithfully.

Copy of the Honorable Discharge for Brister Baker, 1783, from Colored Patriots of the American

Revolution, by William C. Nell. Brister Baker was a Black soldier who fought in the Second Connecticut

Regiment. The meritorious discharge notes that Baker was enlisted into the Army in April 1777 and served

six years faithfully.

The discharge does not make note of the fact that Baker was Black, as would census records in the

next century when biological racism emerged. |

Of course, the issues over which the War of Independence were fought was a matter of complete indifference

to Blacks because they were not involved in commerce. Consequently, there had to be rewards.

Of course, the issues over which the War of Independence were fought was a matter of complete indifference

to Blacks because they were not involved in commerce. Consequently, there had to be rewards.

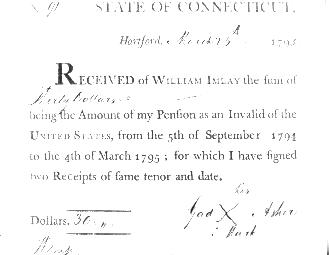

Pensions were

an obvious choice, for they did not make the recipient a property owner able to vote. If the person happened

to be a slave, the obvious thing to do with his pension reward would be to assign it over to their owners to

pay for their freedom. Here is a pension receipt for the Black soldier, Gad Asher, signed with his mark on 4

March, 1795. While Asher was from New Haven at the time, his son, Jeremiah Asher, later moved to Hartford

where his descendents continued to live. |

![[Exhibit contents]](../../bin/top.gif)

![[Back]](../../bin/back.gif)

![[Forward]](../../bin/forward.gif)

|