Objects in the Dark, 1638-1775

Sons and Daughters of Africa |

|---|

For as nearly as long as there has

been this place called Hartford, the sons and daughters of Africa have labored. With their hands and

the sweat of their brows these first sable citizens hewed a place for themselves in this city by the

river. . .

![[sold]](sold.jpg) Colonial newspapers were read mainly by the "bourgeoisie." These owners of productive

property or people

licensed to provide socially valued services needed newspapers to learn about the marketplace in which

goods and services were bought and sold. In fact, much of what was printed in Colonial papers was news

of goods coming into ports or for sale, and, like today, newspapers contained little of the kind of

"news"

(information that serves as a basis for an informed public activity) that is a foundation of democracy. What

was important for the elite in this kind of society was the value of things in the marketplace, and this applied

to people as well. Here, for example, is a Hartford Courant notice of 24 May, 1773, concerning the availability

for sale of a 28-year old mother and her two sons. The owner claims he had too little use for them. He does

not include her husband in the offer so that she might remain with him.

Colonial newspapers were read mainly by the "bourgeoisie." These owners of productive

property or people

licensed to provide socially valued services needed newspapers to learn about the marketplace in which

goods and services were bought and sold. In fact, much of what was printed in Colonial papers was news

of goods coming into ports or for sale, and, like today, newspapers contained little of the kind of

"news"

(information that serves as a basis for an informed public activity) that is a foundation of democracy. What

was important for the elite in this kind of society was the value of things in the marketplace, and this applied

to people as well. Here, for example, is a Hartford Courant notice of 24 May, 1773, concerning the availability

for sale of a 28-year old mother and her two sons. The owner claims he had too little use for them. He does

not include her husband in the offer so that she might remain with him.

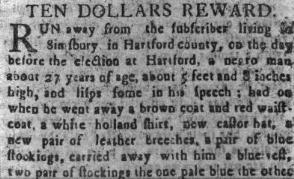

![[reward]](reward.jpg) Naturally, slaves ran away when they could, but the risks must have been enormous, and one expects

younger men were more likely to try it. Unlike today, in Colonial society one could not become socially

invisible by travelling elsewhere or by trying not to stand out, especially if you were Black. Here a 23-year

old "mulatto" (a person who is light-skinned because one of his or her parents was white), named Pero,

is being hunted down. This notice also includes an interesting description of how a slave might have dressed

in 1773. Probably the clothing description was not so much for identification as a listing of the property

that the slave owner would like to recover.

Naturally, slaves ran away when they could, but the risks must have been enormous, and one expects

younger men were more likely to try it. Unlike today, in Colonial society one could not become socially

invisible by travelling elsewhere or by trying not to stand out, especially if you were Black. Here a 23-year

old "mulatto" (a person who is light-skinned because one of his or her parents was white), named Pero,

is being hunted down. This notice also includes an interesting description of how a slave might have dressed

in 1773. Probably the clothing description was not so much for identification as a listing of the property

that the slave owner would like to recover.

![[advertisement for a breeder]](breeder.jpg) These sale advertisements are from the Connecticut Courant in 1773. Most slave sales were of

individuals, but occasionally a group would be sold. Young women were valued for their domestic skills, and

domestic employment remained typical of all Blacks, whether free or black, until the twentieth century

when wage labor opened new opportunities. Young women were also valued as "breeders," as in

this ad, probably because further slave imports to Connecticut were about to be prohibited.

These sale advertisements are from the Connecticut Courant in 1773. Most slave sales were of

individuals, but occasionally a group would be sold. Young women were valued for their domestic skills, and

domestic employment remained typical of all Blacks, whether free or black, until the twentieth century

when wage labor opened new opportunities. Young women were also valued as "breeders," as in

this ad, probably because further slave imports to Connecticut were about to be prohibited.

|

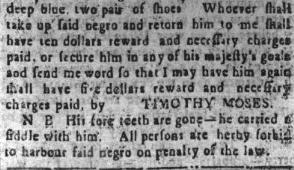

Here is another ten-dollar reward for the return of a young man. Again, the detailed description of

clothing may be as much to ensure a return of all property as to identify the escapee. The fact that

his front teeth are missing (the likely cause of his lisp), might suggest rough abuse, probably from his

owner. Perhaps this motivated his flight. He did take a violin with him, which indicates the importance

of musical culture in slave society. |

In 1690, the Colonial General Assembly passed a law that forbade

any "negro or mulatto servants/slaves to wander out of towne bounds without a pass from

master/mistress." Such a law hints that slaves were indeed roaming about on their own, perhaps with

escape in mind. The run-away slave announcements illustrated here from the Connecticut

Courant of 1774 and 1774 show that this continued to be a problem for the owners a century

later, perhaps because there were by this time significant Black communities in several Connecticut

towns that might provide refuge. On the other hand, the institution of Black Governers, to be discussed

later, would have made it difficult to remain hidden in any such a Black community.

![[Exhibit Contents]](../../bin/top.gif)

![[Back]](../../bin/back.gif)

![[Forward]](../../bin/forward.gif)

|